After raising her children, textile designer, teacher and caterer, Helen Allen, enrolled in the diploma course taught by Anne-Marie Evans in 1996. In 2003, she began to assist Anne-Marie Evans on the diploma course and in 2005, succeeded Anne-Marie as Course Director. Today this 17-year old program is taught by Helen and four other teachers — a botanist from Kew, a botanical illustrator from Kew, and two painting tutors who are also botanical painters. Former students and graduates have earned medals from the Royal Horticultural Society, have artwork included in the Highgrove Florilegium, in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, and are represented in many public and private collections.

While Helen was studying at the English Gardening School, she also worked as a medical researcher. It was during this time she learned that research has to be meticulous and rigorous and this has benefited her approach to botanical painting. During her teaching career, Helen was a an Advisory Teacher in London and was responsible for the teaching of textiles and related crafts in London’s primary schools.

Helen has always loved painting, plants and teaching and at the English Gardening School with Anne-Marie, these three things have come together in a neat package. Helen believes she has been incredibly privileged to have learned from the best and to have taught students who are amazingly talented.

Helen’s own work has been featured in the Highgrove Florilegium twice. Her paintings can also be found at The Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, the Chelsea Physic Garden Archive, the Hampton Court Palace Florilegium Archive and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew Archive and Collection, as well as many private collections.

Please welcome our Feature Artist for September, Helen Allen!

ArtPlantae: Helen, thank you so much for introducing me to your work. Teaching at the English Gardening School and at your own studio keeps keeps you very, very busy! I wanted to begin by asking about the successful program created by Anne-Marie. The program is comprised of three ten-week terms and several projects along the way. Many of us reading this interview have experienced the 5-day version of this 30-week program, having had the opportunity to learn from Anne-Marie herself. Did this program begin as a three-term program? How has it evolved over the years?

Helen Allen: Anne-Marie’s short courses are legendary and beautifully constructed and tailored to get the best results from participants. The short courses are not taught in the same way as our one-year diploma course nor should they be viewed as a shortened version. However, the short course format follows the same 5-step program following the drawing and painting of a chosen flower to it’s final conclusion. It is marvelous to see just how well students, with little or no experience, do in such a short space of time.The diploma program came after the initial short courses and grew out of those. The course began as a certificated program and then became a diploma program in 1996 or thereabouts. The course was designed along traditional methods of art teaching that require much practice. Techniques are learned through exercises that are then applied to plant material. The exercises are building blocks, if you like, and form the secure foundation on which to build towards adding the fine detail.

Over the years I have re-ordered these building blocks in a more logical way and updated materials and tasks. With my teachers, I review and amend program content every year and sometimes during the year if necessary. Student’s work and projects are also monitored on a regular basis; some is self- and group-critiqued and some reviewed by teachers.

Currently class notes and supporting material and images are available to our diploma students by email. We hope to use technology more in the classroom in the future.

AP: What is your teaching philosophy?

HA: I love what I do and want to share this with others. I want my students to learn the excitement of LOOKING at plants and really SEEING, in detail, important diagnostic features. It is only then that the student KNOWS what to investigate, highlight and show in the finished piece of work. It is imperative to OBSERVE and RECORD meaningfully and accurately through careful DRAWING. A good drawing stands a good chance of becoming a good painting. A bad drawing has NO chance at all.

COMPOSITION is the setting for the PAINTING and where BOTANY and DRAWING meet on the page. PAINTING requires hours of PRACTICE and is the ultimate PRIZE.

These are the ingredients which, blended together with care, build CONFIDENCE and INDEPENDENCE.

Learning botanical painting is rather like learning how to make a souffle. There will be mistakes and loss of confidence along the way but if the souffle collapses we have to rescue it and in doing so we learn not to make the same mistake again. This is how we learn to be CONFIDENT.

AP: A number of the program’s students have gone on to make significant contributions to botanical art by way of their participation in florilegia and the inclusion of their work in public collections. Why do you think this is so?

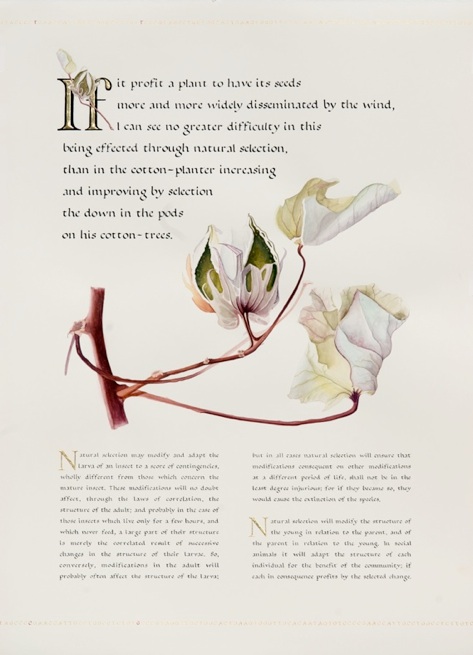

HA: It has become very fashionable for great gardens and collections of plants to be painted for posterity. It is another method of conservation, of preserving plants that may in time become extinct. Artists paint together, and with botanists, make the collections not just scientifically correct but aesthetically pleasing. What a wonderful way to paint. We have always taught in an historical context. This is important, not just to KNOW why we do it but to appreciate the discoveries and developments in science, art and materials over the centuries. It is useful also to know how travel, wars and social history influenced art and the teaching of art. We aim to make students aware of what has gone before and the debt we owe the great artists and botanical artists and illustrators, both historic and contemporary. If we can even begin to scratch the surface of what they did with anything like their dedication and finesse, then we leave a legacy too. I believe our graduates are inspired, have a sense of purpose and are ambitious, not necessarily for themselves, but to leave their legacy for others to see in the future.

AP: The diploma course will begin its 18th year in January. Have you or the English Gardening School considered adding botanical art classes to the school’s schedule of distance learning courses?

HA: We already have a hugely successful and internationally renown Garden Design distance learning course, however I approach learning botanical painting, at a distance, with some skepticism. Technology is a wonderful aid but by the time the painted image has been photographed, saved to CD or hard drive and viewed by several people on as many monitors, the truth is lost. If printed, then we are seriously compromised. Learning in isolation is not helpful. In the classroom original work is seen by tutors and simply watching the way in which a student applies paint can prompt constructive criticism and help. Knowing the students, their approach to their work, their fears and woes, is helpful to their technical and self-development. There is always more than one way to teach and learn a single skill. We need to find the right way for each student and help them individually to attain goals. So many invaluable tips and asides are absorbed in the classroom as well as intelligent critique. I believe that many of these experiences are not available at a distance.

AP: Many people people learn botanical art by picking up a one-day class here and a three-day class there. Often these learning opportunities are separated by several months. Embarking on a serious, structured, long-term study of botanical art is a dream for many and has its obvious benefits. However, even students in established programs can fall behind with their homework. Drawing upon your observations of how students learn botanical art, what is the most effective way students of botanical art can stay on track with their studies?

HA: Firstly, they must be serious in their endeavours and understand that perfection only comes through hard labour. Every stage of the course takes many hours of work. For example, drawing parallel lines would seem a childish pursuit to the uninitiated. However this is how stems are constructed and we all need to be able to observe the nature of the stem and to describe it in pencil, paint or ink with confidence. Whatever the technique, there is no quick-fix solution and they must KEEP UP with and finish the homework set each week.

When homework (assignments) are set, students are advised that they can go home and do the set work OR they can practice it over and over again and then do their homework. They also understand that some tasks take longer than others to perform to an acceptable standard, and individuals learn these techniques at different rates. They learn to critique constructively, ask relevant questions and have their own work critiqued by looking at each others work each week. It is surprising how much one learns this way. If work is not shown, it is impossible for student and teacher to have a meaningful dialogue.

Reading around the botany, visiting art galleries and museums and being aware of our surroundings all influence the way we work and are helpful in the development of our work and skills.

AP: How should students new to botanical art think about paint? (Six colors or as many as your heart desires? Tubes or pans? Palette arrangement, etc.)

HA: AAH! Now here is a most controversial subject. There are as many colour theories as there are hues and all have their good points. It is always interesting to hear the views of other painters. As far as I am concerned, there is no right or wrong paintbox and I will never say NEVER to a student ALTHOUGH I may advise caution. I like both tubes and pans, tubes go further and are easier to mix with water and each other, they are also kinder to paint brushes. But I prefer pans when working on vellum and particularly my old W&N (Winsor & Newton) paints.

I advise a limited palette containing 2 yellows, blues and reds, a magenta, violet, indigo, pthalo green and burnt umber. Other hues are added later on where necessary. Students make paint charts for their boxes, do many paint mixing exercises and quickly become familiar with paints and their properties. These repetitive exercises help students practice and improve their painting skills, whilst providing them with a superb dictionary of colours.

I like the colour bias wheel and descriptions of hues as green blues, orange yellows, violet reds, etc. It is then easy to understand and actually see the relative proportions of primary colours in the botanical subject, to analyse the hues in the paint box and mix accordingly. This is a very simplistic explanation but works well for me.

We advise our students to start with a limited palette to which they add over the year and prefer students to use single pigment paints as when learning and mixing there is less chance of making mud every single time. They will then have a clearer idea of how these colours mix. With just six colours it is possible to make almost any but the very cleanest and brightest of colours. More importantly it is very much easier to mix each colour with the other 5 in turn to see the vast range of colours that are possible. All students begin with the same make and range of colours, rich pigments with sufficient filler to make them easy to mix and to use in washes, and the same white paper so that there is some standardization.

As with all things, the more one works with paints and practices the various techniques required, the more one is able to make choices based on experience. Arranging the paintbox is a personal choice. I arrange mine in RAINBOW order but starting with a green yellow, through reds to violets and onto blues. All other colours come after (this). I now have a red through violets and purples box, a green box, a larger box for yellows and blues, and a box of earths, greys, white and any other stray colours. I also have paint boxes that are restricted to paints made by single manufacturers.

One could pontificate forever. As with technique, one manufacturer of paint or theory does not suit everybody.

AP: Are there noticeable stylistic differences between the botanical art produced in Europe, Asia, Australia and the US? If so, how does the botanical art differ by region?

HA: I think there are. Styles are influenced by culture, education and training. Very often it is the botanical material and placement on the page that gives the game away. I envy the technical ability of many of the Japanese artists, the drawing skills of the Australians and the colour work of the South Africans. American botanical painting is a fusion of many styles in a variety of media and therefore more enigmatic. With huge climatic variation and geographical differences, plant life is also hugely varied. European style is very traditional in it’s approach, but overall remains more true to the traditions and rules of yesteryear whilst continually pushing the boundaries.

I think we are all in danger of missing the point of botanical art, whether it be illustration or painting and maybe even confusing the boundaries between botanical art and the more decorative art of flower painting. It doesn’t matter how good we are in manipulating the tools of our trade or how deep our knowledge of colour theory if we lose sight of why we do it. As botanical painters, what we all need to work towards is the faithful rendition of plants in a three dimensional way whilst capturing the beauty and drama of the subject with subtlety and finesse.

To be more specific will take too long.

AP: Does technology have a place in the creation of botanical art or should this classic art form remain untouched by technology?

HA: I have touched on my concerns about technology in an earlier section. I greatly admire Niki Simpson’s work and am very interested in where it will lead. I believe we need to be receptive to change in materials and technology and see where it leads us, but without losing sight of why we paint botanical. But I think also that a sound classical art training develops hand-eye coordination, develops the mind and the achievement of particular manipulative skills in a way that simply using technology to achieve something similar cannot. However, I do not wish to undermine or denigrate the work of those with technological skills which I neither have nor understand!

I shall be in Boston and look forward to seeing old friends and making new.

Ask The Artist with Helen Allen

Helen welcomes your questions about her work and botanical art. Please post your question(s) below in the comment box. Helen will respond when she is able. Thank you.

You May Also Enjoy:

Art for conservation is Deborah Ross’ passion.

Art for conservation is Deborah Ross’ passion.