Paula Panich is an essayist, journalist, fiction writer, and writing instructor. She has been writing about plants, gardens and other subjects for 30 years.

In 2005, she published Cultivating Words: The Guide to Writing about the Plants and Gardens You Love, the first-ever comprehensive book about garden writing.

Coming soon is The Cook, the Landlord, the Countess, and Her Lover, a book of essays on food, place, memory, and history.

Gardeners, horticulturists and anyone wanting to write about plants or gardens will find Cultivating Words invaluable. In her book, Panich teaches garden writers:

- How to write “how-to” stories.

- How to write service stories.

- How to construct sentences.

- How to write garden-related travel stories.

- How to write clearly.

- How to edit.

- How to look for publications in which to publish articles.

I have read Paula’s book twice and have taken a class with her at the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden.

We have the wonderful opportunity to learn from Paula today.

Please welcome Paula Panich!

Paula, how did your writing career begin? Have you always written about plants and gardens?

I grew up in a house without books. But I loved them. I think there were a few of those Little Golden Books for young children in the house, but the first “real” books to arrive came from my visits to a bookmobile in a shopping center in Dallas, Texas. Yet my grandparents had a bookshelf in a glass-fronted built-in; one of their sons went to college for a couple of years, and the books were his. I still remember the smell of those books. The bookmobile had that same delicious smell of bindings and glue and paper. Intoxicating!

My first “real” book was Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson, by the way. I remember in vivid detail what it felt like to close its back cover. I had finished! I was just thrilled.

My paternal grandparents were from Serbia. They were my primary influences when it came to plants and gardening as I watched them work in their yard. Their lives were unthinkable without these tasks, as mine is today. My grandmother quilted, cooked, baked, sewed, and canned; she was always doing something. Her work was precise, and her precision was imprinted on me. When I began to work on a word processor decades later, the image I had in my mind was my grandmother at her treadle sewing machine.

I think writing often comes to writers because they feel an inner need to rearrange the world. My god! The architecture of sentences! They can change the landscape of perception. But writing also comes to people because they know a great deal about something, and want to share it — like gardens and plants.

What did you want to rearrange?

There was a childhood trauma when I was five. It set up many things in my life. I desperately needed to make sense of the world; but that understanding only came much later. Writers are often people who were set aside in some way, or set out on their own either physically or emotionally.

My first professional gig as a writer came in my 30s when I was pregnant with my daughter. I began writing for Phoenix Home & Garden magazine. (I had been writing publicity stuff for paying clients previously.) But writing journalism was a completely new step and I was exhilarated with the freedom to write about subjects while dipping into my personal cultural capital. I wrote about plants, gardens, and historic preservation. The editor couldn’t throw any thing at me I wasn’t interested in — like crown moulding. I had been a history major, and I had, and still have, insatiable curiosity.

I am always interested in what is beyond, behind under, and over the topic. Back when there was a real publishing industry (wherein people could make a living) and there were categories for writers (e.g., garden, food, etc.). I was placed in the “garden writer” category. But I write about food, history, plants, gardens, landscape, literature, science, and travel — especially travel, where all of these topics come into play.

What topics haven’t you written about that you would like to write about?

I am interested in the interrelationship of things. I am very interested in place and in perception. It occurred to me that both have been the spoken or unspoken platform of my work. Now all of my teaching of writing seems to be about seeing. We can learn to craft a decent sentence — but it is the quality of mind of the writer that counts most.

My interest in seeing — or at least the most concrete example I can give — springs from my interest in contemporary artist Robert Irwin. I began to understand experiential seeing during a six-month experiment that involved weekly visits to his Central Garden at The Getty Center in Los Angeles. I intentionally didn’t take written notes when I sat in this garden, but eventually I began to “take” notes with a disposable camera. Irwin has spoken about seeing and perception for decades. I decided, through these numerous visits over time, to try to understand what he means.

I have written about the experience in a couple of ways. One in an interview with Irwin for the L.A. Times, and another quite different article for Pacific Horticulture. I also taught a class at the Getty Center on writing about the garden in which I used photographs to reveal what I saw and to reveal what was revealed to me. So I learned a lot about seeing. Seeing has a lot to do with the grounding of the person who is doing the seeing. It doesn’t matter if the focus is a garden or a plant or a landscape or a rock.

Irwin is grounded in the philosophy of phenomenology (the study of phenomena and perception), but the act of seeing has been described in philosophy, art, science and medicine. Sixty percent of what we see, according to some researchers, is a mix of our experience and thought. If you and I look at the same plant, we will be able to agree on 40% of what we’re seeing. Everything else depends upon our past experiences.

If we were to describe the same sweet potato, we would describe it differently. I would describe the complicated color, and the texture. But also for me, the sweet potato comes with a story. It is part of my cultural experience because of my grandmother’s experience with it. She told my sister and me that sweet potatoes were her candy in Serbia. So her experience and narrative affects how I see every sweet potato.

You asked how we teachers can encourage people to write about plants in an affective, meaningful feeling, way. I would turn the question around and ask — how is it possible not to do it?

We spend our entire lives constructing our visual world, a mix of our thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

I am not a plant geek. I am interested in stories behind the plants. I think a good way to encourage students to tell stories about plants is to send them out with paper notebooks to describe a plant, but provide them a prompt. For example, This plant makes me feel… . There are hundreds of prompts. The last time I saw a plant like this . . .

Stories shape our brains and are the basis of human culture. There is incredible overlap between the scientific world and the narrative. Don’t forget about young children: stories make their world. Ours too.

People tend to relate to animals better than they relate to plants. The term plant blindness has been coined by researchers to describe the condition that people don’t notice plants as much as they do animals. Drawing helps to encourage one way of seeing. Writing is another. How can artists, naturalists and educators help people “see” with words?

If there is plant blindness, then there is also “writing fear” because of the way writing and reading are taught. I think it’s especially important that the atmosphere in a writing class be supportive, and that fear is dispatched one way or another.

I had what I realize was an important moment in my own “plant blindness.” For two or three years I looked out a window in a tiny shack in the San Jacinto Mountains as I wrote. I actually looked at a certain tree in the midst of a pine forest. I finally realized — after all that time! — I was actually looking at a California live oak. And this tree was only a few yards from the window! Yes — I had “blindness” but in every way that tree conferred its blessing and shelter on me. I drank from that tree. The tree sustained me. Finally — I realized its proper category in the world human beings have made. But it did not wait for me to call it by name to confer its intrinsic goodness.

But back to writing.

Natalie Goldberg wrote Wild Mind: Living the Writer’s Life, and I use some of her writing strategies in classes with kids as well as adults. I ask adult students to get the cheapest notebook they can get — wide rule, 70 pages — to do timed writings. I tell them to move the pen across the page and to not lift it. This helps to take the sting out of putting down words as most people have their high school English teachers, red pencil sharpened, sitting on their left shoulders.

My classes now are more about experience. I started teaching at 21; later, I wanted to focus on urging people to become professional writers. I don’t do this anymore.

I like to bring the rich adult literature about landscape and plants and human response into the mix, even it is just a paragraph. A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold; the books of John Muir; the books of John McPhee. Another book that has captivated me is Keith Basso’s Wisdom Sits in Places. He writes about the Western Apache in Arizona and how their language, psychology, and medicine are rooted in places in the natural world around them.

For teenagers, who always think about sex, the Botany of Desire would be a good book to use. Who could resist the story about how roses got their names? Or the coevolution of the marijuana plant and us?

Sometimes a paragraph or two is enough to open up students’ minds: Here are these wonderful writers, and here are their inventive, wide-ranging minds and concerns. What are yours?

Also, you have to work on yourself as a teacher and as a “person who sees”; that way, you can gently lead students to get out of their own way. Children are already there. They teach you how to move out of your own way.

Addressing plant blindness will require an act of will to interrupt the habitual way of seeing. Harvard professor John Stilgoe wrote a great book called Outside Lies Magic: Regaining History and Awareness in Everyday Places. He tells his students to hop onto bicycles and figure out how the world is put together. It’s a wonderful book. I wish we could spread it around the country, like Johnny’s appleseeds.

Cultivating Words

Paula’s book, Cultivating Words: The Guide to Writing about the Plants and Gardens You Love, can be purchased from Paula through her website for $21.95.

Order

Take a Class with Paula

Paula will teach a two-day class dedicated to writing about plants and place in January/February 2014 at the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden. Cost: $70 for two sessions (nonmembers); $60 members

Learn More

Plan Ahead to Join Paula in New Mexico in 2014

You are invited to join Paula Panich for WALKING SANTA FE: Place, Plants, Spirit, Food ~ A Writing Workshop based on the sights, smells, taste, and spirit of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Founded in 1610, the city sits amid the natural beauty of Northern New Mexico; it has a deep and rich history braided by the traditions and beliefs of the three cultures now at home here. November 13-15, 2014.

Cost: $300

Paula’s classes have been added to Classes Near You > Southern California.

Read Full Post »

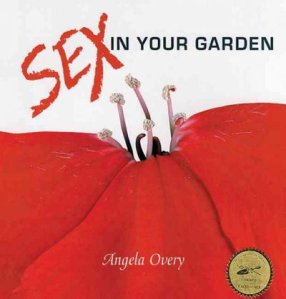

Plant reproduction can be as sensitive a topic as human reproduction.

Plant reproduction can be as sensitive a topic as human reproduction.

a kneaded eraser, a metal single-hole sharpener, a 6” clear ruler in inches and metrics, a Dick Blick zipper pencil bag to hold all the loose bits, and a spiral-bound sketchbook. Oh, and a folder full of handouts addressing how to’s, basic botanical nomenclature and diagrams, a bibliography and a few of the plant family pages I had developed for the Field Museum.

a kneaded eraser, a metal single-hole sharpener, a 6” clear ruler in inches and metrics, a Dick Blick zipper pencil bag to hold all the loose bits, and a spiral-bound sketchbook. Oh, and a folder full of handouts addressing how to’s, basic botanical nomenclature and diagrams, a bibliography and a few of the plant family pages I had developed for the Field Museum.