Animals are fun.

They engage us with their movements, have big round eyes, have cuddly fur and come in intriguing shapes, sizes and colors.

Plants, however, just sit there.

These truths, plus other interesting facts about how people perceive organisms are discussed by Petra Lindemann-Matthies in “Loveable” Mammals and “Lifeless” Plants: How Children’s Interest in Common Local Organisms Can Be Enhanced Through Observation of Nature.

Lindemann-Matthies evaluated a program created to enhance children’s knowledge of biodiversity. The program, Nature on the Way to School, was administered at 525 Swiss primary schools from March – June 1995 to celebrate the “European Year of Nature Conservation.” In her paper, Lindemann-Matthies makes the point that environmental education studies investigating student knowledge of the environment are different than educational studies in biodiversity focusing on “children’s direct observation and investigation of local wild plants and animals” (Lindemann-Matthies, 2005). Lindemann-Matthies states that the outcomes of biodiversity education have not been studied extensively and it is this topic that is the focus of her research.

Lindemann-Matthies (2005) says dedicated efforts to teach biodiversity to children must be taken to take advantage of young children’s interest in learning about living organisms. In her paper, she refers to biodiversity studies completed in Austria and Germany. In these studies, it was determined that incorporating outdoor experiences with classroom instruction was more effective at enhancing student awareness of local plant and animal species, than simply talking about local plants and animals in the classroom (Lindemann-Matthies, 2005).

The Nature on the Way to School program was created by the Swiss conservation organization Pro Natura. Classroom material and instruction was provided to teachers. Teachers ordering these materials were invited to take part in Lindemann-Matthies’ study. The program’s hands-on activities called upon students to engage in activities such as drawing plants and animals, caring for invertebrates like snails and earthworms in the classroom, and recording what was observed while walking to school (Lindemann-Matthies, 2005). Of the many classrooms in which this program was administered, Lindemann-Matthies evaluated the program’s effectiveness in classrooms where the teacher completed and returned the pre- and post-test questionnaire required for Lindemann-Matthies’ research. Her final study group was composed of 248 classrooms and over 4,000 students ages 8-16.

Research questions addressed by Lindemann-Matthies (2005) were:

- Which plants and animals do children like best, and which organisms are especially valued on their way to school?

- Did the educational program Nature on the Way to School change children’s preferences for species?

- Did the age and sex of the children influence their preferences for species and did age and sex influence the effect of the program?

Results

When students were asked which plants and animals they liked best before participating in the Nature on the Way to School program, students listed garden plants or decorative plants such as roses, tulips and daffodils and few made reference to the local plants of Switzerland (Lindemann-Matthies, 2005). After the program, the number of students listing local plants (especially wildflowers) increased. The increase observed in the experimental group was significantly higher (11.4%) than in the control group (2.6%) (Lindemann-Matthies, 2005). When students were asked to name their favorite animals, students listed pets (especially cats, dogs and horses) more often than local Swiss animals prior to the study. After the study, students still listed pets more often than local animals (Lindemann-Matthies, 2005). When it came to plants, children’s preferences for plants were not influenced by sex or age (Lindemann-Matthies, 2005). This was in contrast to Lindemann-Matthies’ findings about preferences for animals where it seems more girls like pet animals and more boys like exotic animals (e.g., lions and tigers) and wild animals (e.g., squirrels and deer).

Lindenmann-Matthies (2005) observed that the plants and animals students claimed to appreciate the most were directly related to the plants and animals to which they were exposed. So if children were exposed mostly to garden variety plants, they referred to these plants more often when asked which plants they liked (or appreciated) the most.

Lindenmann-Matthies (2005) also observed a positive relationship between the number of program instruction hours received by students and their appreciation for the wild plants and animals of Switzerland. The more instruction students received, the more they demonstrated an appreciation for local flora and fauna. On average, teachers from the 248 participating classrooms spent 17 hours teaching the Nature on the Way to School program, with the actual hours of program instruction ranging from one hour to sixty hours across all classrooms (Lindemann-Matthies, 2005).

Teachers in 144 of the 248 classrooms incorporated the program’s Nature Gallery activity into their curriculum. This clever activity called upon students to serve as interpreters for their favorite local plant or animal. In this activity, students were asked to frame the plant or animal they liked best during their walk to school. More than 50% of the items framed by students were wild plants, followed by plants whose identification were unknown (16.2%), which was then followed by garden variety plants (15.5%) (Lindemann-Matthies, 2005). The wild animals framed by students were represented by anthills, spider webs and birds nests (13.7%) (Lindemann-Matthies, 2005). After framing their subject, students were encouraged to spend one week providing information about their subject to fellow students, to parents, to anyone walking by and in some cases, the media. Students had to explain why they chose their subject and while students cited many reasons for selecting their subject, most students chose to frame a subject because of its beauty (22.5%), “likeability” (20.2%) or some specific feature students found interesting (Lindemann-Matthies, 2005). The plant framed most often was a dandelion and Lindemann-Matthies (2005) reports that the students framing this plant tended to do so because it was “growing in unusual places.” Lindemann-Matthies states the Nature Gallery activity was the “highlight” of the Nature on the Way to School program.

Citing the observations above and many other observations described in her 22-page paper, Lindemann-Matthies (2005) concludes:

- The Nature on the Way to School program was successful at making students more aware of the diverse number of plant and animals species in their local area.

- There appears to be a strong association between awareness and preference. In this program, as students became more aware of local plants, their preference for local plants increased.

- While student preference for pets did not change, their preference for pet animals decreased with the number of program instruction hours received. Lindemann-Matthies (2005) proposes that the average number of instruction hours received (17 hours) is not enough to increase student appreciation for local wild animals.

- Even successful programs have sobering limitations. When students were asked what they would have liked to frame in a Nature Gallery if given a choice, students “still preferred ‘loveable’ animals, in particular mammals from countries other than Switzerland.”

To learn more about Lindemann-Matthies’ research, visit your local college library to pick-up a copy of this paper or purchase it online for $34.

Literature Cited

Lindemann-Matthies, Petra. 2005. “Loveable” mammals and “lifeless” plants: how children’s interest in common local organisms can be enhanced through observation of nature. International Journal of Science Education. 27(6): 655-677

The Book of Leaves: A Leaf-by-Leaf Guide to Six Hundred of the World’s Great Trees

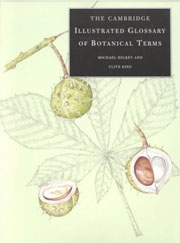

The Book of Leaves: A Leaf-by-Leaf Guide to Six Hundred of the World’s Great Trees The Cambridge Illustrated Glossary of Botanical Terms

The Cambridge Illustrated Glossary of Botanical Terms